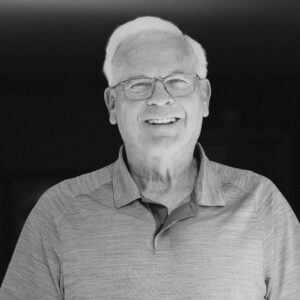

Robin Selvig – Outlook, Montana

Robin Selvig grew up in a town most Montanans have never heard of and even fewer have ever seen. Outlook, a tiny farming community on the Hi-Line in the northwestern-most corner of the state, had about 150 people when Selvig was a kid and the local school educated roughly 50 of them. His graduating class had 15 students.

“There were eight schools in our conference,” he remembers, “and only two still have a school now.” The others have been swallowed up by the economics of modern farming – kids don’t return to take over the family operations, equipment gets more expensive, and small towns fade away. But back then, Outlook was alive, held together by ranching, farming, and the one thing that could warm a town through long, cold winters: sports.

In small schools, everyone participates in every activity. “You’re all in music, you’re all in the school play,” he says. “You grow up together, you know everyone.” Sports were the center of the community. “Everybody went to the girls’ games in the fall, and everybody went to the boys’ games in the winter.”

Women’s sports weren’t an afterthought, they were central. In the late 1960s, years before Title IX would require equality in sports programs, the small towns of eastern Montana were already planting the seeds of what would become a national transformation.

Selvig saw that change up close. The second oldest of eight kids, he had three sisters who loved sports. After Title IX passed, one got a single year of high school athletics, another got two, and the youngest finally got all four. “It’s amazing how backwards we were not that long ago,” he says. “My mom would’ve loved sports, but she never had the chance.” Girls in his generation weren’t allowed to run laps in PE, weren’t considered capable of long-distance running, and were often limited to cheerleading.

Title IX changed everything. “Transformative,” he says. “For society, not just sports.”

The Importance of Strong Mentors

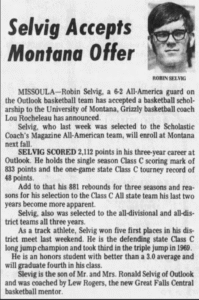

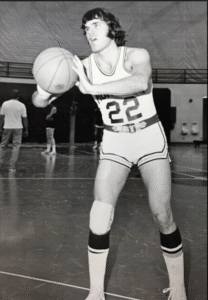

After high school, Selvig left Outlook for the University of Montana, where he played for legendary coach Jud Heathcote, who later won a national championship with Magic Johnson at Michigan State.

“I learned basketball from Jud,” Selvig says. “He was brutal. He pushed me so hard. But he made me a better basketball player. Nobody practices as hard on their own as they do when someone’s pushing them, it’s how you learn what you’re capable of.”

Selvig never intended to coach women’s basketball. After college, he believed he had been hired for the boys’ job in Plentywood, but when the boys’ coach delayed his retirement, the superintendent asked Selvig if he’d take the girls’ team instead.

He took it seriously from day one.

“I couldn’t help but take them seriously,” he says. “It’s no different than coaching anybody else.”

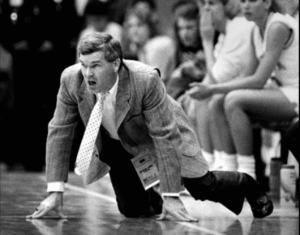

Three years later, still in his 20’s, he became the head women’s basketball coach at the University of Montana, a job he would hold for 38 seasons.

Under Selvig, the Lady Griz became one of the great stories in college basketball: national respect, Big Sky titles year after year, one of the most loyal fan bases in the game, and one of the winningest coaches in women’s basketball history.

His success was rooted in relationships and in treating every player like she mattered. He cared deeply about each kid’s experience, often worrying most about the ones who hardly played. “There are only five starters,” he says. “But they are all important to me, and I think they knew that.” For Selvig, it was just as essential that the players who rarely played felt as valued as the ones who did.

Opening Doors: The First Full-Ride Scholarship for a Native American Player

Selvig’s commitment to opportunity extended to all Montanans. Early in his tenure, he became the first coach in the nation to offer a full-ride Division I basketball scholarship to a Native American woman, Malia Kipp from Browning. He wasn’t trying to make history, he simply recognized talent and believed Montana’s Native communities deserved the same opportunities as anyone else.

“I wasn’t giving them a gift,” he says. “They were good enough to play. And Montana needed to open doors for Native kids.”

Recruiting Native players taught Selvig far more than basketball. It taught him about courage, culture, resilience, and the challenges his players faced both at home and at the university.

“It was eye-opening,” he says. “Getting to know them and their culture, it was really meaningful. But I didn’t realize at first how hard it was for them to come here.”

Over the years, Selvig recruited many Native American athletes who became key players for the Lady Griz and role models across the state. His willingness to open the doors of a major program changed the trajectory of countless young women, and signaled to Montana that Native talent belonged on the biggest stages. For his efforts in recruiting Native players, Selvig became one of the few non-Indians to be inducted in the Montana Indian Athletic Hall of Fame in 2008.

The Heart of a Montanan

Maya Angelou’s famous line could easily sum up Selvig’s career: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Selvig never claimed a secret formula. He simply showed up as his best self, a deeply caring, demanding coach who gave his players permission to show up as their best selves, even when their best selves were complicated. “I was goofy. I apologized many times because in the heat of the action, I was an idiot sometimes. But I think that’s because they were all important to me, and I think they knew that, no matter what was happening.”

A small farming community shaped him, Hi-Line winters forged him, Jud Heathcote sharpened him, and the women he coached gave him decades of joy, heartbreak, purpose, and meaning.

“I don’t know what else I’d have done,” he says. “Coaching made sense.”

In the end, what mattered most wasn’t the wins.

“Being part of a team makes it bigger than yourself,” he says. “That was always the point.”

A team that spans generations – from small gyms in Eastern Montana to roaring crowds in Missoula – all connected by the work ethic, humility, and community that gave a boy from Outlook a lifelong outlook on what really matters.