When I asked Brooks about his favorite teacher growing up in Billings, he warned me about his answer. “Most people, if I said ‘Mrs. Will’, would recoil in horror and start shouting expletives. She was mean.”

But sometimes “mean” is the opposite of what it seems in your 13-year-old mind. Instead, it can be a kind of toughness that sets a high standard for your life, a window that lets you see what you’re capable of.

“I have to say more than any teacher, she left a mark on me. She wasn’t just teaching English . . . it was about personal responsibility, self-confidence, self-esteem in a way that I hadn’t felt before. Her standard was so tough, it was so high, and I rose to that.”

He tells a story about 8th grade, when he was always forgetting something. He would get to class, realize he didn’t have his book, and sprint back to his locker before the bell rang. After one of many such incidents, Mrs. Will looked at him and said, in a strict voice, “Get it together.”

Impressively, Brooks took that to heart. “I was like, she’s right. I do need to get it together.”

He not only never forgot his book again, he took her high standards with him, becoming the kid who was always prepared. By the time our paths crossed in high school in the early ’90s, I knew him as not only the most prepared person in every class, but also highly organized, well-dressed, witty, and on his way to becoming valedictorian.

But the put-together kid I met at 16 was the culmination of a childhood marked by fear. He told me that on his first day of elementary school he cried at his desk while the other kids were at recess. That feeling stayed with him through most of his school years, and although he got better at presenting something else on the outside, he usually felt fearful on the inside.

When I asked why, he said he always felt different from the other kids. “I wasn’t interested in any of the usual trappings – hunting, fishing, outdoorsiness. But I also think it was being afraid of . . . people. The other kids. I always gravitated toward teachers.”

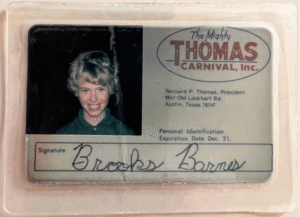

During summers, while his classmates were running around together, he traveled throughout northern Montana and southern Canada from carnival to carnival with his family, who owned a concession business. In an article he later wrote for the New York Times, he described that world this way:

“Among the carnival crowd, it was the opposite. I was accepted, even celebrated. When I was still in grade school, my parents allowed me to roam alone when they were working, which was all the time. They knew that Slim, who ran the Ferris wheel, or Chief, the mustachioed merry-go-round operator with no teeth, or Ruby, a dwarf who performed as the World’s Smallest Woman, would drop everything and eviscerate anyone who messed with me.”

When I asked if kids were mean to him at school, he didn’t hesitate. “Definitely.”

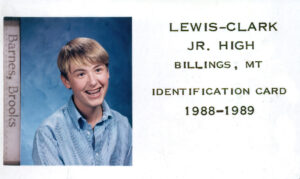

He said he started withdrawing around 4th grade, when the bullying intensified, and that it peaked in junior high. It didn’t help that his family moved across town just before 7th grade, forcing him to start at a new school without knowing anyone. To make matters worse, he had hip surgery at the beginning of that year and started school in a wheelchair, then spent the first half of the year on crutches.

He also had a perm, for reasons he still can’t explain or understand, like many of the hair decisions of the ’80s.

The lunch lady had to carry his tray and would set it down next to what he described as the “other cast-offs,” kids he listened to but didn’t talk with. The week he got off his crutches, he also got his hair cut. Toward the end of that week, one of them asked, “Hey, where’s that girl that was sitting here?”

Another kid answered, “The one on the crutches?”

“Yeah, what happened to her?”

Brooks replied quietly, “I don’t know.”

He went along with it, one of those moments that only becomes bearable with distance.

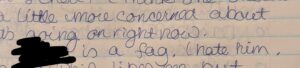

Before talking with Brooks, I came across my seventh-grade journal from a different Montana town and was embarrassed by what I read. I had used the word “fag” casually, interchangeably with “jerk,” without understanding its weight. It was so normalized in my middle school that I wrote it in a journal I turned in to my English teacher. She didn’t say a word.

When I admitted this to Brooks, he was understanding, given the time we grew up in. But he also named the damage. “It’s corrosive, right? And you don’t really realize how much so until later. There were no real cultural references that were positive. You just can’t show yourself in any way because that’s a danger, that’s a risk.”

So he learned to ignore the constant corrosion, careless kids like me throwing around harmful words, unaware of how deeply they could land or how long their effects might last. Now, with the clarity he wishes he’d had then, he knows that “98% of the time, if someone is being cruel, it’s a comment on them, it’s not a comment on you.”

But that clarity wasn’t available in the early ‘90s. As welcoming and diverse as Billings Senior was, no one was openly gay. “Coming out” wasn’t part of our vocabulary or understanding.

And yet, despite all of it, Brooks says that being in close proximity to people from all walks of life taught him something essential: your perspective changes when you actually get to know someone. “That almost always, if I moved closer to somebody, my perspective on them changed . . . if we’re in a 2-person study group, we’re just two kids.”

Public school doesn’t automatically make you open-minded, but it gives you practice – often excruciating, uncomfortable practice – living beside people you didn’t choose, people who look, think, and act differently than you do. And that practice shaped the impulse Brooks would eventually build a life around: asking questions, listening closely, and wanting to understand people beyond first impressions.

When he talks about becoming a journalist, he describes it as a kind of rescue. His mom encouraged him to join the student newspaper, and once he did, “Something magical happened, which was that I could talk to people if I wasn’t myself, right? If I was calling as ‘Brooks Barnes from the Bronc Express,’ I could ask you anything and not have this feeling of excruciating visibility.”

It wasn’t Brooks calling. It was the newspaper.

Journalism gave structure to his curiosity, an instinct he believes is underrated and one public school helped cultivate. Many of his colleagues at the New York Times come from the same prep schools and Ivy League paths. They’re excellent journalists, he says, but their curiosity can be narrower after a lifetime spent inside the same bubbles. When you’re always talking to the same kinds of people, it’s easy for your perspective to shrink.

For Brooks, learning beside people from all walks of life didn’t just shape him; it sharpened his curiosity and made him the kind of journalist who knows the truth rarely lives inside those familiar circles.

There isn’t a tidy public-school moral here. Public school can be brutal, but it can also lay the foundation for becoming the best version of yourself. Learning to live and learn alongside people who aren’t like you matters more than we like to admit.

And sometimes, what you once took for meanness was actually a teacher who recognized your potential. Years later, when you’re a New York Times reporter staring at a deadline and a blank page, you may find yourself reaching back for that voice.

“Mrs. Will, I need you right now.”

And you get it together.